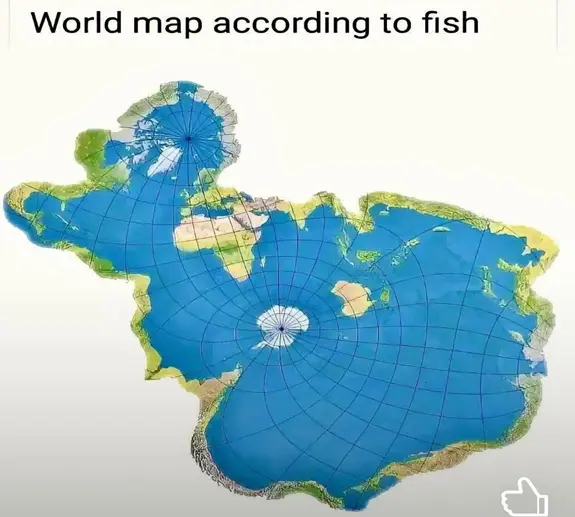

The World as Fish See It

What looks like an obscure map is a profound truth about how fish perceive our planet. Humans see the world divided by lines, nations, and borders. Fish do not. Their world is continuous — a single, flowing ocean shaped by currents, temperature, salinity, and light. Land is not home; it is an interruption.

For ocean fish, the real “world map” is not about continents or countries — it is about zones of survival. They live by gradients: the sunlit epipelagic zone where plankton bloom, the mesopelagic twilight, the deep scattering layers, and the polar feeding grounds where nutrients surge. These zones are connected by invisible highways — ocean currents that transport life across basins.

Species like tuna, salmon, and sharks migrate thousands of kilometres across these vast networks, guided not by maps but by instinct, magnetism, and temperature. To them, the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans are one interconnected system — a living body, not a collection of political territories.

And yet, we humans try to manage fish. We draw lines on the sea — Exclusive Economic Zones, quotas, and boundaries — pretending that fish understand our borders. In truth, we do not manage fish; we manage people — fishers, industries, and consumers — because only human behaviour can be regulated. The ocean itself ignores our paperwork.

It is worth remembering, too, that this view only reflects ocean fish — the saltwater species that inhabit over 70% of Earth’s surface and contribute to the planet’s life support systems. The ocean produces 50–85% of the world’s oxygen through marine photosynthesis (Field et al., 1998; Falkowski, 2012), and seafood provides vital protein for over 3 billion people (FAO, 2024).

But beyond the ocean, there is another world — the freshwater realm of rivers, lakes, and estuaries. These waters make up less than 0.01% of Earth’s total water (Gleick, 2019) yet are home to over 15,000 freshwater fish species, half of all known fish (IUCN, 2020; WWF, 2021). Many of these species are now under threat from habitat loss, pollution, and overuse.

So, while the “fish’s-eye map” may seem humorous, it actually reveals the real architecture of our biosphere: a blue planet where the ocean is the true world, and land is merely the edge — a temporary refuge for the air-breathing creatures who try to manage it. Why were we called Earth and not Ocean?

References:

- FAO (2024). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024. Rome: FAO.

- Field, C. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., Randerson, J. T., & Falkowski, P. (1998). Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science, 281(5374), 237–240.

- Falkowski, P. (2012). Ocean Science: The power of plankton. Nature, 483, S17–S20.

- Gleick, P. H. (2019). Water resources. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology. Springer.

- IUCN (2020). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- WWF (2021). The World’s Forgotten Fishes. WWF Report.