As published in the Neos Kosmos today Losing the catch: How Greek fishing operators suffer from government policies - Neos Kosmos

How Victoria’s Focus on Recreational Fishing Has Left Our Seafood Future Adrift

The unfolding crisis for Greek family seafood businesses in Victoria marks a turning point in this state’s fishing story. Once the backbone of Melbourne’s fresh fish supply, these small, sustainable operations, many founded by Greek migrants in the mid-20th century, are being forced out by government initiatives that heavily prioritise recreational fishing at the cost of commercial livelihoods.

The result is a shrinking local seafood sector, no plans for essential seafood into the future, and a growing disconnect between Victorian consumers and their coastal heritage.

Greek heritage at the heart of Victorian fishing

For generations, Greek family fishers have been central to Australia’s seafood identity. Arriving from the Mediterranean (Kythira, Kastelorizo, and Crete, etc) with deep maritime knowledge, they introduced important innovations (e.g. Danish seining) and established the infrastructure, installed a high-level work ethic and created the reputation of Victoria’s wild-caught seafood industry. Communities from Queenscliff to Lakes Entrance thrived thanks to these families supplying Melbourne markets and restaurants with local snapper, whiting, scallops, calamari, flathead, and more. Their businesses anchored a full supply chain from the bay to the plate, supporting livelihoods and a living heritage of skill and care.

How Government Policy Turned the Tide

The tide began to turn in 1997 with the Victorian Government banning the dredging of Commercial Scallops when Rex Hunt used his media power to promote the concept that dredging was badly impacting Port Philip Bay (PPB) and thus his beloved recreational fishing. At the time Premier, Jeff Kennett, was persuaded that there were more votes in supporting this notion, despite little to no scientific evidence.

The recreational fishing lobby now had a face and a voice in the media and promoted ‘we fish, we vote.’ That was the end of scallop dredging in PPB. The protestations of the industry agitated the government to the point that when it changed the regulations they ensured that the only way of harvesting scallops would be through diving and hand harvesting.

Only one diving licence was issued but approximately 90 vessels and up to 20 processing companies and countless people were put out of business. Kennett went on to lose the next election!

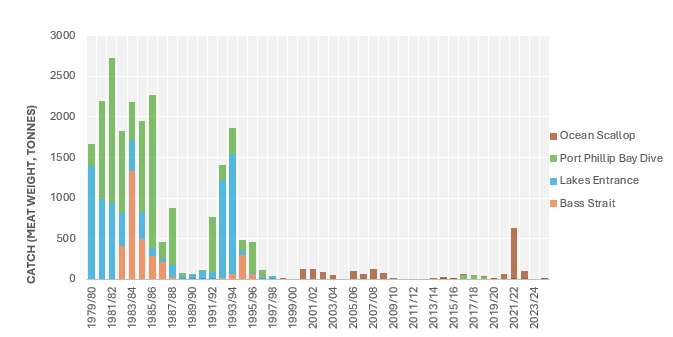

Figure 1: Time series of catch (meat weight, tonnes) in the Victorian Scallop Fishery. Port Phillip Bay was closed to commercial fishing in 1997, and in 1998 the licences for Bass strait and Lakes Entrance were combined to be called 'Ocean Scallop'.

Source: Victorian Fisheries Authority (website, 2025).

Go Fishing Victoria Strategy

Since 2014, more than $35 million has been spent phasing out commercial netting in Port Phillip Bay and the Gippsland Lakes to “get more families fishing” for recreation.

While these policies proved popular among recreational anglers, they devastated many coastal and Greek-Australian businesses that fished responsibly for generations. The removal of the 700-tonne Port Phillip Bay net fishery alone meant the loss of dozens of family businesses and an annual supply of hundreds of tonnes of fresh local seafood. Many of these small-scale operators were among the most sustainable in the country.

Melbourne chefs publicly protested that “Victorian-caught” fish would disappear from menus, replaced by air-freighted seafood with a higher cost and carbon footprint. Industry groups warned that up to 600 tonnes of local seafood supply would vanish annually.

Policy Gaps, Compliance, and Local Supply

The consequences were predictable: rising reliance on interstate and overseas seafood, higher prices, and vulnerability to global supply disruptions. Nationally, around 70% of the seafood Australians eat is now imported. In once-busy fishing towns, knowledge, jobs, and cultural identity have faded as fishers left the water, often without meaningful recognition of the legacy they leave behind.

Meanwhile, 2025 budget cuts led to the closure of key enforcement offices and a sharp reduction in fisheries compliance officers. This, in turn, increases pressure on marine health, as policing large numbers of recreational fishers (who are not required to report their catches) is increasingly difficult.

This was forecast by a Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) study by Fishwell Consulting which found that commercial fishing in Port Phillip Bay posed only minor ecological risks.” It also cautioned that government-driven increases in recreational fishing were likely to raise sustainability challenges, undermining the perception that removing commercial operators benefits the environment.

A professional industry can be held accountable for catch and sustainability through carrot/stick management, but a loosely monitored recreational sector places an unrealistic burden on remaining officers and the system overall.

The contradiction of “sustainability”

From a consumer perspective, Victoria’s policies now contradict national trends in sustainable food production. While other states are investing in traceable, low-impact local supply chains, Victoria’s reduced local catch has led to higher prices and less clarity about seafood origins.

Ironically, the small-scale Victorian commercial fishers who were displaced were among the most sustainable in the nation. Research confirms that Port Phillip Bay’s fisheries had minimal ecological impact before closure. The current policy trajectory instead drives demand toward overseas producers and whilst they must meet food standards they are not creating sustainable jobs and opportunities for Victorians, nor does it create confidence for consumers with seafood security.

Time for a Policy Reset

Importantly, the decline of Victoria’s local catch does not stem from irresponsible behaviour by socially aware recreational anglers. Most are passionate custodians of the bays and oceans. Rather, it is government policy settings and a lack of meaningful support for small-scale commercial fishers that have created this imbalance.

Stakeholders from industry, consumer, and conservation groups agree: Victoria needs a new approach. There is room in our large bays and oceans for responsible recreation and commercial harvest. Science-based, limited commercial quotas and a focus on truly low-impact gear (like longlining and handlining) can allow heritage fisheries to survive while safeguarding our marine environment.

Investment in Victorian aquaculture can also help fill part of the gap, but wild-caught fish remain irreplaceable in flavour and cultural significance, especially for migrant communities whose identities are tied to the sea.

Honour Heritage, Secure the Future

For Greek-Australian fishing families, the loss of access to local waters is more than an economic blow, it is a threat to living culture, food knowledge, and community wellbeing. If Victoria is to secure a truly sustainable seafood future, we need a government willing to revisit its approach, valuing commercial fishers alongside recreational interests, investing in compliance, and supporting food security for all Victorians.

Ultimately, the sea is a shared resource owned by the community: government policies relating to managing the resource should reflect the needs and history of all who care for it. There is plenty of space for all to enjoy the ‘treasures’ that the bays and oceans provide us. It should not be those holding the loudest voice, but a greater understanding of the shared resource come election time.

Comments

No comments yet.